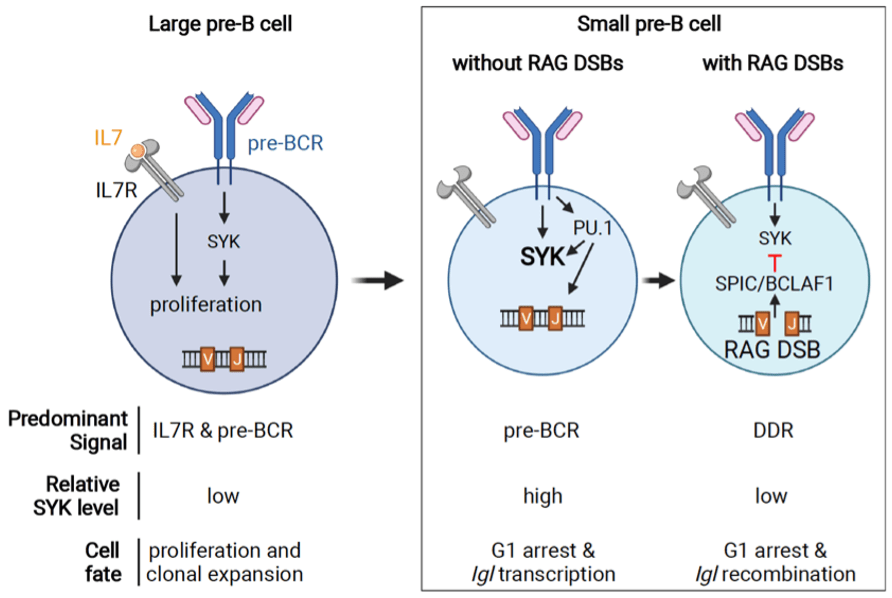

Lymphocyte development is precisely controlled to enable clonal expansion and expression of a diverse immunoglobulin receptor repertoire, which proceeds through DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) generated by the RAG endonuclease. These two dichotomous, but interdependent processes, are managed through the cooperation of diverse cellular signals to prevent cells with DSBs from entering cell cycle where they could be aberrantly repaired as translocations. During early B cell development, the pre-B cell receptor (pre-BCR), through activation of the SYK kinase, coordinates both the proliferative expansion of pre-B cells and the assembly of immunoglobulin receptor genes. Negative regulation of the pre-BCR is required to ensure cell cycle arrest and limit the number of DNA breaks generated during immunoglobulin receptor gene assembly. Indeed, unopposed pre-BCR signaling, particularly increased SYK activity, drives proliferation and leukemic transformation. However, the mechanisms that repress SYK and pre-BCR signaling are not known and remain a critical gap in our understanding of B cell maturation. We have identified a novel cell-type specific program activated by signals from RAG DSBs that suppresses SYK and inhibits pre-BCR signaling. We have found that RAG DSBs induce a novel transcriptional repressor complex comprised of the ETS-family transcription factor SPIC and the transcriptional regulator BCLAF1. SPIC/BCLAF1 opposes the ETS transcriptional activator PU.1 in pre-B cells to suppress SYK, an effector of pre-BCR signaling, thereby inhibiting pre-B cell proliferation.

Ongoing projects include:

- Defining the function of this RAG-mediated DDR program in maintaining pre-B cell checkpoint

- Determining how deficiencies in this DNA damage-mediated feedback circuit result in initiation of pre-B cell leukemia.

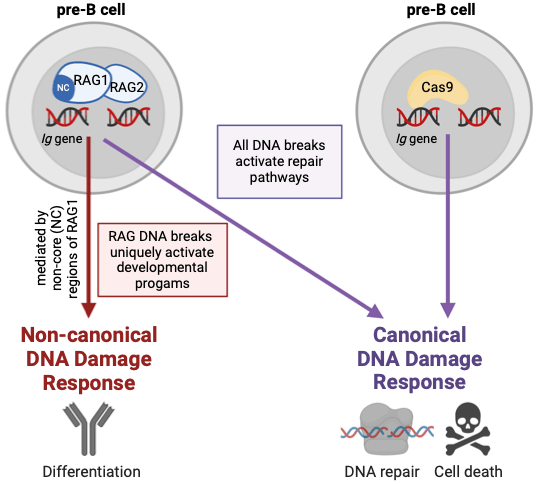

RAG DSBs present a unique DNA injury, in that they occur in the setting of other developmental programs and must integrate with these processes for continued B cell maturation. By contrast, non-RAG DSBs, which are detrimental to B cells, need to be distinguished to prevent errant development. The mechanisms that differentiate RAG vs non-RAG DSBs are not known. Both RAG and non-RAG DSBs activate ATM to direct canonical DDR-mediated repair pathways. RAG DSBs also initiate ncDDR to mediate developmental programs. Using an inducible system to generate Cas9-mediated DSBs in early B cells, we recently determined that non-RAG do not trigger this developmental program. Additionally, we’ve identified that the N-terminal region of RAG1 is necessary for induction of the RAG DSB-specific DNA damage response.

Ongoing projects include:

- Determine of the function of N-terminal region of RAG1 in activation of DNA damage responses

- Identification of RAG1 binding partners that function in DNA damage response regulation

- Determination of role of genomic location in regulation of DNA damage responses

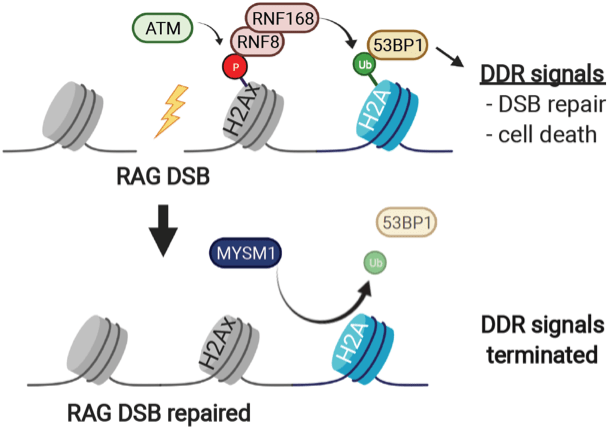

Patients with deleterious variants in MYSM1 have B cell lymphopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress. In preliminary studies, we find that MYSM1-deficient B cells have increased activation of DNA damage signaling even in the absence of exogenous genotoxic agents. MYSM1 is a deubiquitinating enzyme that removes ubiquitin from histone H2A to promote gene expression. In B cell progenitors, MYSM1 regulates expression of transcription factors that promote differentiation. However, this activity of MYSM1 does not account for the B cell lymphopenia or the increased radiosensitivity in patients with MYSM1 mutations. We have recently demonstrated the MYSM1 functions to terminate DNA damage signals that have been activated by RAG-mediated or irradiation-induced DNA breaks. MYSM1 does not regulate generation or repair of DNA breaks but rather functions to extinguish DNA damage responses after DSBs are fixed. In the absence of MYSM1, DNA damage signals persist despite normal DSB repair, which results in continued activation of downstream cellular responses, including cell death and cell differentiation pathways.

Ongoing projects include:

- Determination of cell-type specific activities of MYSM1

- Determination of mechanism of MYSM1 activation in DNA damage response

- Investigation of MYSM1 deubiquitinase activity in DNA damage responses

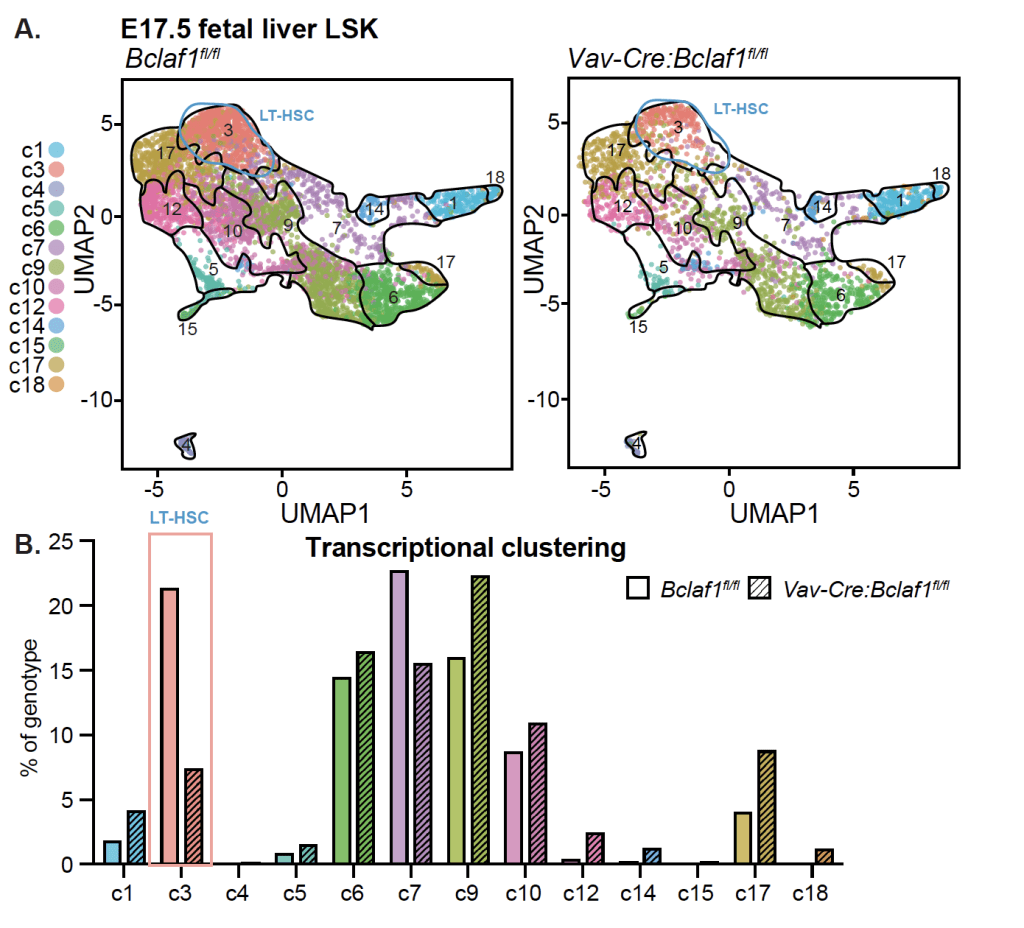

Bone marrow stem cells have a unique ability to continue to divide throughout life. This self-renewal capability is critical for sustaining production of blood cells but also has important roles in leukemia. Leukemia cells often hijack these pathways to drive growth of the malignant cells. The programs that control stem cell self-renewal change during development from infancy to adulthood, which may contribute to the differences in pediatric and adult leukemia. The underlying mechanisms that determine these developmental changes are not known. We recently identified BCLAF1 as a novel regulator of HSC self-renewal activity and development. In fetal mice, Bclaf1 deletion results in a marked reduction in HSC numbers. The reduced HSC numbers persist in adult mice; but there is no additional decline or development of bone marrow failure with aging. Thus, BCLAF1 has critical functions in fetal HSC development but is not essential for maintenance of adult HSC homeostasis. Notably, both fetal and adult Bclaf1-deficient HSCs are defective in reconstituting hematopoiesis in competitive transplantation experiments. These studies support a function for BCLAF1 in regulation of HSC self-renewal during hematopoietic processes that depend on extensive HSC expansion, namely fetal HSC development and repopulation of hematopoiesis after stem cell transplant. Leukemic blasts also rely on mechanisms that support rapid expansion while maintaining an undifferentiated state. Our goal is to understand how BCLAF1 regulates stem cell development and how these pathways are altered in leukemia.

Ongoing projects include:

- Characterizing the role of BCLAF1 in normal stem cell function throughout development

- Determining the mechanism by which BCLAF1 regulates stem cell self-renewal

- Determining the role of BCLAF1 in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)